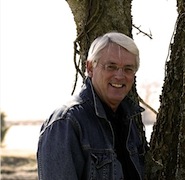

I lost a friend last week. No, it wasn’t a surprise. The tumors in his brain finally got the upper hand. The fact that I knew it was coming makes it no easier to accept. You can see from the title above that I still think of him in the present tense, and I suspect that I always will. That’s his character.

Although I have known him for well over half my life, there are others who can give the particulars of his life, fully lived, far better than I. There have been times when I’ve not seen him for stretches of time, but when we reengage it’s as if I’ve seen him every day of my life. In many ways our lives seemed to take parallel paths, but there were important differences as well. I think it was the differences that made our friendship worth the effort.

Robert (Bob) Norman Sharpe was born a few months before me in 1943. We were babies of one war and shaped to manhood by a much later war. He lived his three score and ten, but it wasn’t enough. There should have been more. He and I shared the lower middle class roots of a working class family, but neither of us saw our beginnings as a limit to our aspirations. We both went to small state colleges, but the formal education we received only served to scratch an itch of intellectual curiosity that would continue to grow and would last a lifetime. We both married good women; most would say far better than we deserved, and these women stayed with us through thick and thin, often more thin than thick. Just like the vows said. In fact, Bob told me that after he returned from his tour in Viet Nam, that his wife, Nan, saved his life. Saved him from himself.

Bob and I both joined the Army when the Army needed fodder for the relentless mill of war. We both pinned on our gold bars at roughly the same time, with the prospect of fighting in the jungles of Southeast Asia a virtual certainty. We had different strategies for survival. He opted for the the Special Forces, presumably the best preparation one could get for combat. I, on the other hand, had the good fortune to transfer to the Adjutant General Corps and receive training in computers and systems design. No one ever killed a systems engineer, at least not in combat. Both strategies worked, but our experiences were markedly different. Bob, like most combat veterans, did not talk much about the reality of his experience, but every now and then, something would surface, usually after a long night of too much mizuwari in a Tokyo bar. One evening he spoke of an increasing sense of invulnerability in combat. He hadn’t been killed; therefore, he couldn’t be killed. In fact, he said that once or twice he was driven to prove his presumption by standing up, without cover in the midst of a firefight. Waiting for the bullet that never came.

Bob was a leader of men. And his men loved him whether in combat, in business or on the banks of a trout stream. I suspect this type of respect of one man for another has much to do with characteristics we don’t often discuss. Bob cared for his friends as he cared for those for whom he had responsibility. He was not reticent of showing how he felt. It’s now a little trite to say it, but Bob “led from the front.” He never asked of anyone what he himself could not or would not give.

Bob and I both were recruited out of the military by a then small computer company that was willing to take a risk on us if we would take the risk of the company surviving. It did and we did as well. We both went through entry level training in programming and systems design, where I had a slight advantage, but ultimately we both wound up in sales as products of an intensive sales training program for which we were selected to the first class. We traveled our assigned areas and ultimately the world, seeking business for our company and new experiences and advancement for ourselves. It is said that “a rising tide lifts all boats,” and certainly we were the beneficiaries of a rising tide, but we did more than our part in using that rising tide to our advantage.

Bob’s favorite author, to whom he introduced me, was H. L. Mencken, and he could quote situationally appropriate bits and pieces of the Mencken philosophy at the drop of a hat. I heard from him more than once, “…every man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands, raise a black flag, and begin slitting throats.” But his bookshelf and his reading wasn’t limited to Mencken. Bob was one of those rare types who not only read extensively, but retained almost everything he read. He could recite stanzas from Shakespeare as well as lines from Mencken. He knew Bob Dylan cold. His telling of jokes was legendary. Some people can, most can’t. He could. He would mimic the brogue of a corporal of the guard from the north of England as easily as a sharecropper from Louisiana. Thing about Bob’s jokes is that they were always on point to the conversation and they were believable. And he could, and did, keep it up all night.

Bob collected first edition books as well as wines from around the world. He and I would often prowl the wine auction in Dallas looking for overlooked Burgundies or super Tuscans that were a bargain, or that we just had to have. He built a great cellar and enjoyed it immensely. I, on the other hand, bought as he did, but I couldn’t bring myself to drink the really good ones. Bob noticed my reluctance to pull the cork on a great bottle and once said to me, “Gary, there are two types of wine people in the world. Those that drink from the top of their cellar, or others like you who always drink from the bottom.” You know, he was right. I just had to throw away three cases of really good wines, collected over the years, that had aged out and gone bad sitting at the top of my cellar. That would never have happened to Bob.

Bob, like all of us, had his idiosyncrasies, but even here, his were larger than life. I remember a story told by a long time hunting partner about a pheasant hunt in Nebraska. At the end of the day their group repaired to the local pub for some refreshing libations and an opportunity to recount the shots made, missed and not taken. Another group, most likely locals, was at a table nearby. They were eating pickled jalapeños out of a jar and chasing it with a cold brew. Wanting to show up the Texas group, they offered the jar to Bob’s table and one of their number ate not one, but two jalapeños and passed the jar back with a smirk. To counter, another of the local chaps, ate the last jalapeño, then chased it not with a beer but a swig of the pickling juice in the jar and passed the jar back to the Texans. Bob had had enough. He grabbed the jar, chugged the remainder of the juice then took a bite out of the jar. The locals said not a word, but went about their business. That was Bob.

As I was cleaning out the wines that I had let go bad in my cellar, I found a 1.5 liter bottle of 1986 Beaulieu Vineyards, Georges de Latour, Private Reserve, 50th Anniversary. It was still packed in a presentation case on which Bob had inscribed a note on the occasion of my 50th birthday. As I said, Bob knew his wines and he knew his man.

I’ve thought a couple of times over the last twenty years of opening that wine, perhaps to impress others, perhaps to enjoy myself. But I never did, and I’m glad. I think I’ll save it for when I might see Bob next, or if, as I suspect, I don’t, at least I will think of him and what he meant to me.