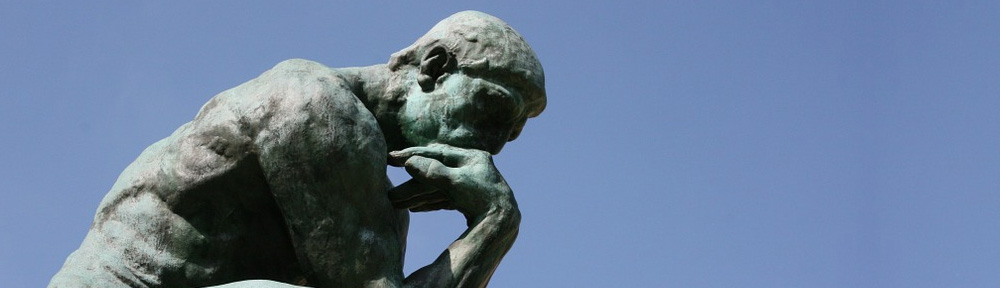

The Two-tailed Swallowtail Butterfly is magnificent in its own right, but even more so when seen as but one element in a complex cycle of nature

I’m always on somewhat shaky ground when I write about the natural world. Even though I’ve posted before on such disparate topics as dragonflies, pissants, skunks, monkeys, and, of course, birds, I’ve never tried to make anything coherent out of these separate natural elements. Recently, however, I’ve begun to contemplate the meaning of it all. By all, I mean how one bit relates to the other, and then another, and finally becomes a whole.

Lately, S. and I have been rising early and spending time in the garden in the relative cool of the summer morning. It’s more or less mindless work. Pulling weeds, picking whatever needs picking and talking about how we’ll do it differently next year. One can’t spend much time thusly without noticing the frenetic activity of the bees, wasps, and butterflies flitting from one plant to the other; doing their business and moving on. While I was familiar to an extent with the role of bees and wasps in the process of pollination, I did not know, or it had not registered on me, that butterflies discharged the same function.

In that readers of my sporadic posts have intellect well above the average citizen, you would probably know what I did not. There are three types of pollination. Biotic, entomophilic, and, zoophilic. See, I told you that you would probably know this, but just in case your memory is a little rusty, these in turn connote pollination from plant to plant, pollination by insects, and finally, pollination by birds or bats. I’m sure you also recall that pollination is the process by which pollen is transferred in plants to enable fertilization and sexual reproduction.

No, I’m not going to get distracted by a digression in to the reproductive behavior of plants, but I must remind you of the next step in the cycle, because this is where the butterflies come in. Actually, butterflies are more or less indifferent to pollen and collect it only as a by-product of their hunt for nectar which is the fuel for their flight. The pollen becomes attached to receptors on their body as they probe for nectar and then goes with them as they hip hop to the next plant often of the female variety. The pollen, which is actually a coarse powder containing the secret ingredient that produces the male plant sperm, is thence deposited on the pistil (you’ll have to figure out what the pistil is on your own) of the female plant. This interaction causes germination and produces a pollen tube which transfers the sperm to the ovary of the female plant. Then nine months later, baby plants are born. No…not exactly, but you get the idea.

Back to butterflies, the key actors in all this. They are of the order Lepidoptera (I knew that you would want to know) and in addition to playing a critical role in the cycle of nature, are quite amazing critters. There are, according to some who presume to know, 28,000 or so butterfly species. Pinning down the number is a little like determining how many angels can dance on the head of a pin….it depends on what you’re willing to believe. Let me offer you a few more factoids on our pretty, big winged friends.

You already know that butterflies are important agents of pollination, but probably did you know that they carry heavy (for them) loads of the stuff over great distances and periodically engage in great migrations over thousands of miles. You and I also both know that there’s plenty of creatures that achieve extraordinary feats of long distance migration, but none of the others weigh in at .41 grams soaking wet. I’ve been trying to work out how much .41 grams is in a measure that we understand, but I’ve failed miserably, so I’ll only say they don’t weigh very much at all. Of all the interesting characteristics that I’ve discovered is that some of them have taste sensors on their feet. Wow. Think of it. They can check out what stuff tastes like by stepping in it, and only then, decide whether to stick their proboscis in it and chow down.

Ok. I realize I’m wandering around here. What I really wanted to get to is….you guessed it….metamorphosis. Until now, I mistakenly thought that metamorphosis was a bad play written by one of those Greek guys that they made us read in freshmen literature.

But no, metamorphosis, as practiced by butterflies and a few other critters in the insect and amphibian worlds, is the process by which the animal develops after birth by a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in its body through cell growth and differentiation. In words that you and I understand, they are born as one thing a then, presto change-o, they become something else. I’ve read a lot about it in the last couple of days, but I still have no real idea how it happens, it just does. It’s only one of the many little things that occur in the natural world that nature slips in on us. Tell me, if you can, the connection between the Swallow-tailed butterfly at the top of this post and the creepy, crawly caterpillar that eats your flowers. They are one and the same DNA wise, but one has metamorphosized into the other. At some level, I suspect that we all knew that this kind of stuff happened in nature, but when you see it up close in personal it has much more of an impact, doesn’t it.

I realize that I haven’t really achieved my objective of connecting all the dots in nature or created a coherent whole out of bits and pieces, but at least I’ve gotten some idea of a part of it. From a caterpillar to a butterfly to a butterfly playing a vital role in the sex lives of plants and propagating another generation of brightly colored flowers. That’s enough for today, I think.

Yes, I know that The Metamorphosis was a novella written by Franz Kafka who is in no way a Greek.